If you’ve ever read a headline about “the UN condemning human rights abuses” or “Geneva launching an investigation into violations,” you may have wondered who, exactly, was doing the talking. Was it the UN Human Rights Council? The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights?

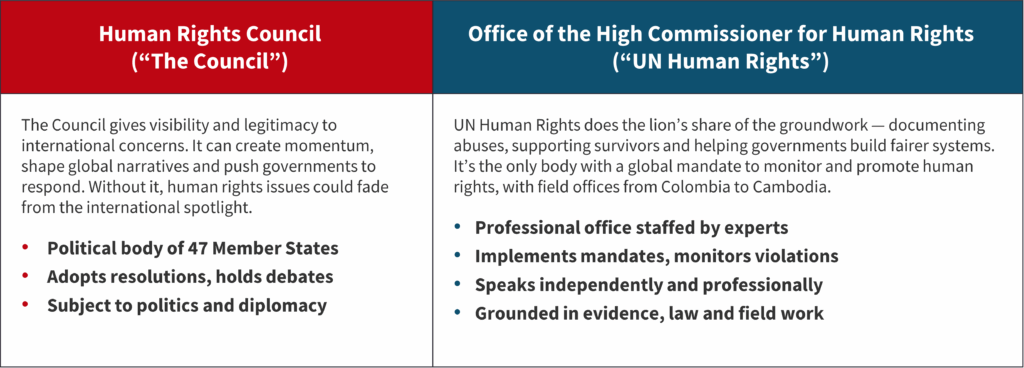

Understanding the difference between these key bodies — one political, the other operational — is essential to knowing how human rights get advanced (and sometimes stalled) on the world stage.

Check out this explainer for a deeper dive into the definition of human rights.

The Council: The UN’s Political Body for Human Rights

Think of the Human Rights Council as the political arm of the UN’s human rights machinery. It’s where Member States come together to debate, negotiate and pass resolutions about human rights issues around the world.

Based in Geneva, Switzerland, the Council was created in 2006 to replace the former Commission on Human Rights. It’s comprised of 47 UN Member States, distributed by region and elected by the UN General Assembly for staggered three-year terms. The most recent U.S. term concluded in 2024.

The Council is where states can publicly scrutinize each other’s human rights records through tools like the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), adopt resolutions, create commissions of inquiry and give mandates to experts to investigate urgent issues such as atrocities against civilians in Syria or Sudan. Right now, the Council has 11 active country-specific investigative bodies and more than 40 mandates on cross-cutting themes.

The Council is a deliberative body, which means outcomes can be shaped by geopolitics and alliances, which often raises the ire of critics. Nevertheless, the value of the group lies in its visibility, its agenda-setting power and its ability to create mandates for substantive human rights investigations. Its discussions are also streamed live on YouTube.

The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights: The UN’s Human Rights Engine

On the other hand, there’s the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights — or simply UN Human Rights. UN Human Rights is responsible for promoting and protecting human rights globally, empowering civil society actors, advising governments and integrating a human rights perspective across all UN programs. In effect, it’s the operational side of the house.

Made up of human rights professionals, lawyers, economists, statisticians, field monitors, policy experts and more, the Office was established in 1993 to serve as the UN’s leading authority on human rights. It’s headed by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights — currently Volker Türk — with more than 90 field offices worldwide.

The mandate of UN Human Rights is explicit and extensive. It includes monitoring human rights violations in countries; supporting special rapporteurs and experts appointed by the Council (there were more than 60 as of 2024); providing technical assistance to governments through training police, advising on judicial reform and drafting laws; and maintaining the UN’s human rights treaty bodies like the Committee Against Torture or the Human Rights Committee, which review compliance with international treaties.

Importantly, UN Human Rights speaks with independence. The High Commissioner can — and often does — call out powerful countries’ abuses, regardless of alliances. In fact, Volker Türk has recently issued statements condemning military rule in Myanmar and unlawful detentions in Venezuela.

How Do They Work Together?

Though the Council and UN Human Rights are separate bodies, their work is deeply intertwined.

The Council can, for example, request investigations, monitoring or reports from UN Human Rights or create mandates for country-specific or thematic rapporteurs. The Council can also invite the High Commissioner to brief members of the Council or issue updates. UN Human Rights must, then, follow through on those Council requests.

Meanwhile, the High Commissioner acts independently, speaking out on issues not taken up by the Council — a crucial function in politically fraught contexts where consensus can be hard to reach.

Why the Distinction Matters

This distinction isn’t just a matter of semantics. Confusing the two can obscure who’s accountable — and who isn’t.

When a UN report is issued on Venezuela, Russia or Xinjiang, it’s written by UN Human Rights staff or independent experts, not the Council itself.

Just as important, when politicians say they want to defund the Human Rights Council because of who’s sitting on it, what they often end up doing is cutting the UN Human Rights’ budget — gutting the very staff investigating violations and training governments to do better.

In 2024, for example, several U.S. proposals to cut UN human rights funding threatened to halt fact-finding missions in Sudan, curtail support to treaty bodies and scale back field operations in dozens of fragile countries. Most of that work was being done not by diplomats at the Council, but by UN Human Rights experts on the ground.

Why the U.S. (and the World) Needs Both

In short, the Council and UN Human Rights together make up much of the backbone of the global human rights system. For the United States, engaging with both is crucial. When the U.S. sits on the Council, it helps shape the agenda, push for action and defend our allies. When it supports UN Human Rights, it helps ensure human rights actions are meaningful, credible and effective.

The Takeaway

So the next time someone mentions the UN and human rights, pause and consider: Which human rights body are they referring to? And remember that, as Volker Türk reminds us, “Human rights are a low-cost, high-impact investment to mobilize people for peace, security and sustainable development.”

“Human rights are a low-cost, high-impact investment to mobilize people for peace, security and sustainable development.”