July 28, 1945: As a light rain fell over Washington,

history was made inside the U.S. Capitol

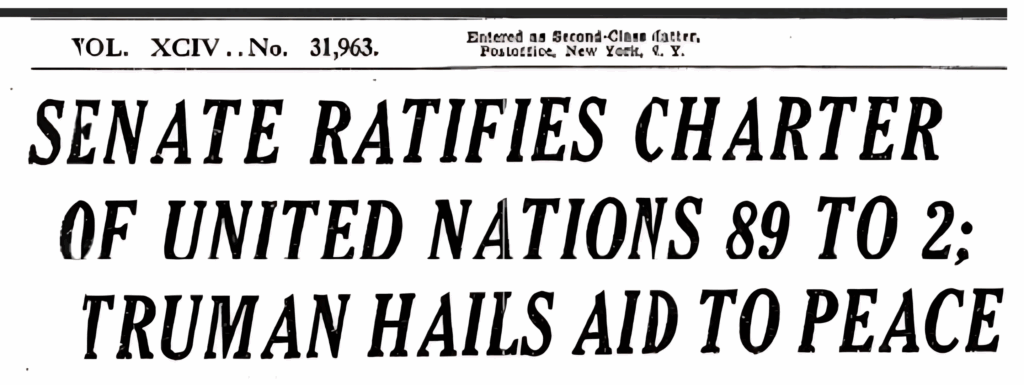

Just three months after the guns of World War II fell silent in Europe, the Senate voted 89 to 2 to ratify the Charter of the United Nations. In that bold, bipartisan act, the U.S. became the first major power to join a new global institution devoted to “saving succeeding generations from the scourge of war.”

“We the Peoples”: A Vision Born in America

The UN was, in many ways, America’s bold idea, hatched aboard a U.S. warship off Newfoundland in 1941, where President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill envisioned a framework for peace in a postwar world — the Atlantic Charter.

Even the name “United Nations” was coined by Roosevelt. According to a diary entry by his close aide, Daisy Suckley, FDR thought it up one night in bed, then burst into Churchill’s room — who stood towel in hand, straight from the bath — and declared, “The United Nations!” To which Churchill, still dripping, replied: “Good!”

“FDR got in to his bed, his mind working and working. Suddenly he got it — United Nations! The next morning, the minute he had finished his breakfast, he got onto his chair and was wheeled up the hall to WSC [Winston Churchill’s] room. He knocked on the door, no answer, so he opened the door and went in… he called to WSC and in the door leading to the bathroom appeared WSC, ‘a pink cherub,’ FDR said, drying himself with a towel and without a stitch on! FDR pointed at him and exploded: ‘The United Nations!’ ‘Good!’ said WSC.”

Daisy Suckley, Special Assistant to President Franklin D. Roosevelt

By 1945, Roosevelt’s vision took shape in San Francisco, where 50 nations gathered to draft the UN Charter. The U.S. didn’t just host the conference — it helped shape the language, embedding principles of sovereignty, human rights, diplomacy and the rule of law.

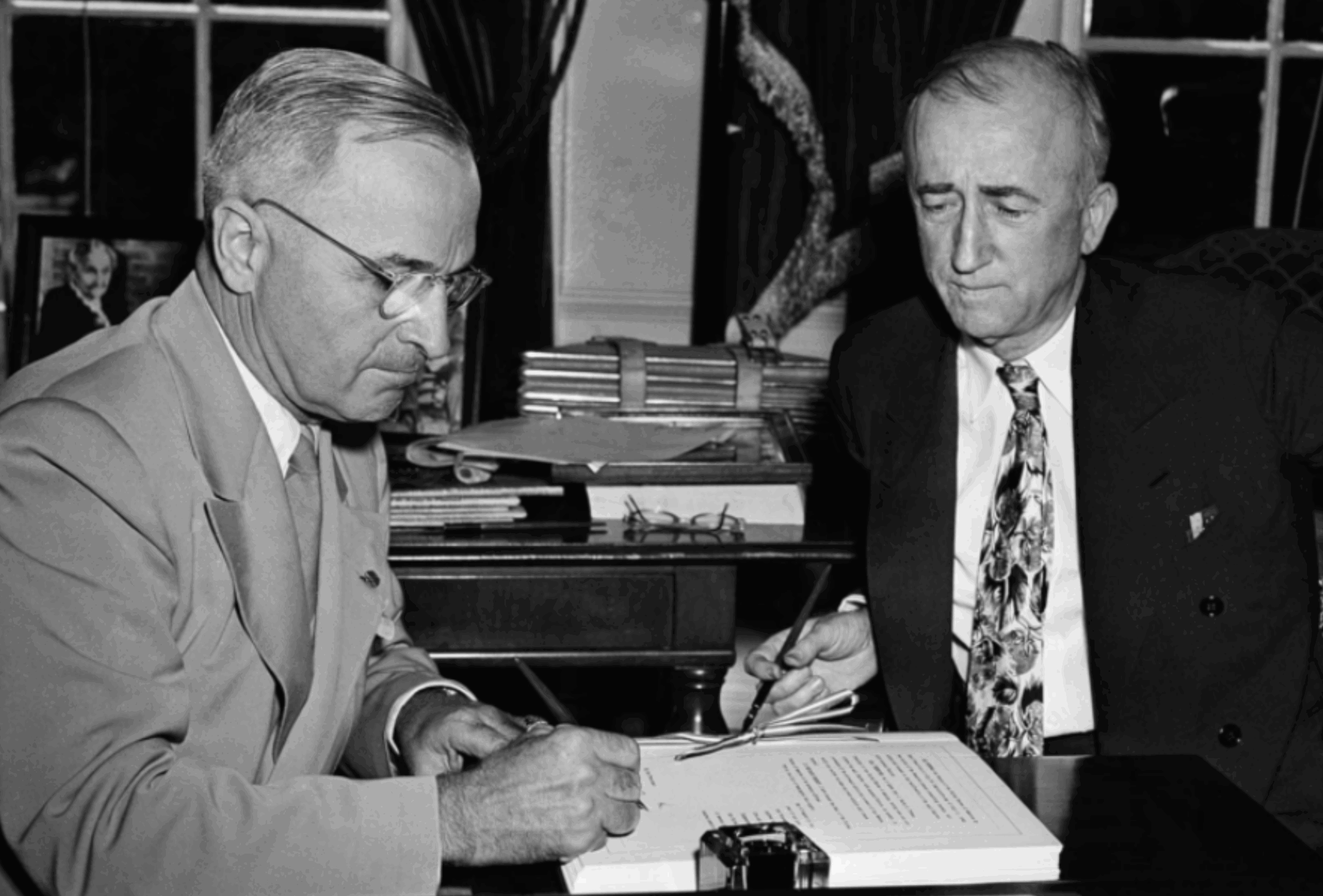

At the signing ceremony in the session in San Francisco’s Herbst Theatre, President Harry Truman — newly sworn in after Roosevelt’s death — issued a warning to the world: “If we fail to use [the UN Charter], we shall betray all those who have died so that we might meet here in freedom and safety to create it.”

“If we fail to use [the UN Charter], we shall betray all those who have died so that we might meet here in freedom and safety to create it.”

President Harry S. Truman

The Senate listened.

From Barbershop Towels to Senate Ovations

Treaties don’t often sail through the Senate, but the UN Charter did — moving from committee to final vote in just five weeks. One of its fiercest champions was Senator Arthur Vandenberg, a Republican who had once opposed U.S. engagement overseas.

“Isolationism died with Pearl Harbor,” he later wrote.

“Isolationism died with Pearl Harbor.”

Arthur Vandenberg, U.S. Senator

Only two senators opposed ratification. One of them, California’s Hiram Johnson, registered his dissent from the Senate barbershop. As the clerk arrived to record his vote, Johnson gave a muffled “no” from beneath a steaming towel.

The moment was electric. The Senate gallery was packed with reporters, generals, Cabinet officials and foreign dignitaries. When the vote passed, the chamber erupted in applause and an extended standing ovation — a rare breach of decorum and a testament to the day’s significance.

A Vision for Peace

Some argue the UN was right for 1945 but ill-suited for today’s challenges. What they forget is that the U.S. Senate ratified the UN Charter before World War II had ended. In fact, Japan’s surrender wouldn’t come for another two months. And on August 8 — the day President Truman formally signed the Charter — headlines were dominated not by diplomacy, but by war crimes: the creation of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, a direct precursor to today’s International Criminal Court.

Even The New York Times front page included a reminder of tragedy closer to home: a bomber had crashed into the 79th floor of the Empire State Building, claiming dozens of casualties. There were also mentions of growing Chinese influence, rising tariffs, increased gold smuggling, the rise of nonstate actors and plenty of pieces that could easily be mistaken for today’s top news.

Fact is, the world then was as uncertain as it is now. And that’s exactly why the UN was created.

As U.S. Secretary of State Joseph Grew warned at the time, “Millions of men, women and children have died because nations took to the naked sword instead of the conference table to settle their differences.”

“Millions of men, women and children have died because nations took to the naked sword instead of the conference table to settle their differences.”

Joseph Grew, U.S. Secretary of State

Why It Still Matters

Nearly 80 years later, that founding spirit is more relevant than ever. In a fractured world, the UN remains one of the best hopes for peace — and it’s worth remembering: it was America that showed up first, voted big and said yes to a better world.