The Origins of a Global Health Movement

At its inception in 1948, the World Health Organization identified two primary functions – technical assistance to individual counties and cooperation across and within nations to strengthen health services. Since then, the WHO’s scope has grown in tandem with the need and demand for a central, global health body. Today, the institution leads international research, procurement, surveillance, and – arguably most critical – preventing the spread of cross-national infectious disease.

The work of the WHO has unquestionably saved millions of lives and improved the quality of life for billions more. Its achievements are nothing short of extraordinary, including the eradication of smallpox and provision of vaccinations for preventable diseases like diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, measles, and tuberculosis. Reduction of all-cause mortality directly attributable to WHO action is incalculable.

Moreover, because health extends beyond the parameters of the clinic walls, the WHO can be credited for navigating the intersection of global health, politics, and socioeconomics in ways no other health agency has achieved – largely because no other body is centrally positioned within a larger organization where its influence ensures consideration of health in all policies.

There’s simply no equivalent organization on the planet with the legitimacy and scope to coordinate global disease prevention and response. The WHO’s 194 members rely on it as a neutral, third party that provides an arena to convene, shape norms, and lead international research.

Challenges and Opportunities

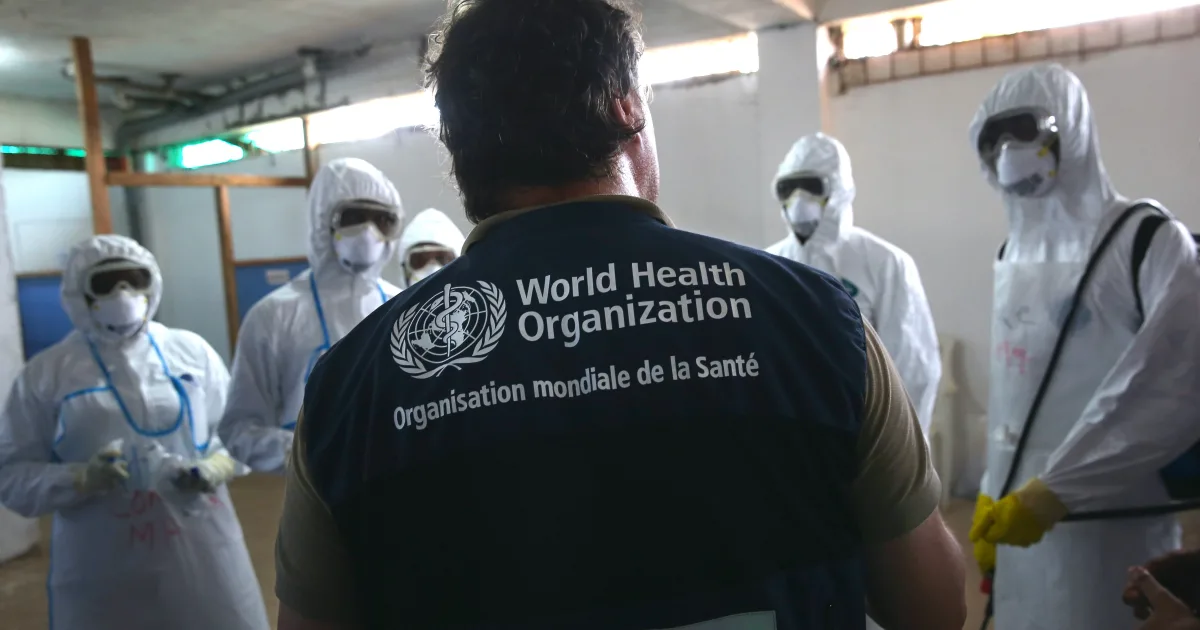

And yet, there’s also no question that the evolution of the WHO has had its challenges, and these, too, deserve to be explored. Many rightly point to the WHO’s inability to respond quickly during the 2014 Ebola outbreak, and revelations continue to emerge about WHO’s role in what amounted to a cascade of global shortcomings over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. To its credit, however, the WHO itself chose to commission an independent evaluation led by Helen Clark and Ellen Sirleaf to examine the WHO’s pandemic response, in order to identify areas of necessary improvement.

Alternatively, some rebuke of the WHO rests on more anti-globalization, isolationist worldviews, concerned that the breadth of the WHO’s mandate make it prone to overreach, while others fear its expansiveness renders the institution too unwieldy to be effective. This isn’t unlike other member-based international organizations that must balance the requirement for global policies with the need for its member states to adhere to these same policies.

All these debates, however, prove a critical point. The world wants a global health quarterback. These questions about the role and efficacy of the WHO are consistently grounded in a desire for more thoughtful action, more committed funding, and more effective, transparent coordination. So rather than opining on whether and how the WHO may be weak, global debate signals that the world – including the U.S. – needs something much stronger.

Right now in Geneva, we can build that. Here’s how.

1. The U.S. must lead in our commitment to funding.

The WHO coordinates its entire global public health mandate with a budget of less than $2.5 billion a year – the equivalent of a single, large U.S. hospital system. In fact, it operates with $2 billion less than the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s annual budget. Member States at the WHO are debating how to ensure the organization is funded to meet the challenges of the 21st century, like what proportion of the budget should be set aside for programs and how much flexibility is needed to react to crises. The U.S. is the largest contributor to the WHO, and programs like the Global Polio Eradication Initiative have been successful because of our leadership. We need to make sure the organization remains fit for purpose. Because as the COVID-19 pandemic showed, a global health emergency can cause economic losses in the multi-trillions of dollars and Congressional intervention in the form of emergency stimulus topping $5 trillion.

2. Americans need to know how U.S. commitments keep our citizens safe.

U.S. engagement in the WHO is good for Americans. From providing guidance on the seasonal flu vaccine and prequalification of diagnostics and treatments, to strengthening the health systems of countries to deal with diseases before they become a global pandemic, the WHO is a bargain. We know that a disease can circle the globe in hours. Our full cooperation enables other countries – especially in the developing world – to build capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to health threats. In a globalized world, this helps ensure the health security of Americans and our economic and trade interests.

Simply put, it’s better to stop diseases at their source before they become costly and deadly outbreaks. And, more often than not, a healthy country is a stable country.

3. We need to back meaningful reform of the WHO.

The pandemic accord that’s currently being drafted in Geneva and slated for adoption under Article 19 of the WHO Constitution in May 2024, is a prime opportunity to show U.S. leadership in the WHO to shape a more accountable, transparent, and fully-funded global body. The agreement – brokered by an intergovernmental negotiating body – is a direct response to countries that saw opportunities for improvement in the global COVID-19 response and are committed to better preparedness and coordination in the future. The recommendations that will be included in the final agreement are based on sound science, independent evaluation, and multilateral engagement. It is in U.S. strategic, humanitarian, and economic interests to remain fully engaged at the negotiating table throughout this process.

There’s never been a more fitting moment for the U.S. to assert global leadership and embrace the WHO as a partner in our own health policy – and the world’s.