A 27-Million Person Tragedy

Human trafficking isn’t just a tragedy — it’s big business. An estimated $150 billion industry, trafficking exploits more than 27 million people every year, according to the International Labour Organization. Victims are forced into labor, sexual exploitation and organized crime in every corner of the world — from downtown Bangkok to small-town America.

And while trafficking may operate in the shadows, its consequences land squarely in the daylight.

Just ask the roughly 17,000 victims identified within U.S. borders in 2023 — or Colorado native Megan Lundstrom, a trafficking survivor who had 45 encounters with law enforcement before her perpetrators were caught.

“It made no sense at the time,” Lundstrom says. “But in hindsight, I understand that the systems just weren’t in place then. I don’t think law enforcement was ‘talking across silos’ to really understand how to address the problem.”

Today, Lundstrom heads the U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline. A far cry from her years of exploitation, she now works alongside local, national and global partners to ensure the systems she once lacked are available to others.

Among those global partners: the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), which leads the international fight against trafficking.

America’s Global Partner

With a 120-person team, UNODC supports countries with data collection and surveillance, legal reform, law enforcement training and survivor services. Much of that work is made possible by its largest funder: the United States.

“The U.S. deserves credit for a lot of what’s been accomplished,” says Ilias Chatzis, chief of UNODC’s Human Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling Section. “But we have a lot more to do.”

That urgency stems from the evolving nature of the crime. “More violence. More cybercrime. More organized networks exploiting new technologies,” Chatzis warns. “We have to keep up.”

According to UNODC’s 2024 Global Report on Trafficking in Persons, identified victims have increased 25% since 2019. A staggering 38% are children. More than 60% of women trafficked globally are exploited sexually, while nearly 40% of men are forced into labor.

And traffickers are getting more savvy, increasingly turning to digital platforms to recruit.

In one notorious case in the Philippines, a single raid freed 600 victims from a cyber scam compound. They had been forced to pose online as romantic partners or IT agents and were brutally beaten when they didn’t meet quotas. UNODC believes dozens of similar centers operate across Southeast Asia, raking in between $16–$37 billion annually.

“These are not the victims you expect,” Chatzis says. “They’re IT-skilled, educated, tricked into coming to another country and then trapped.”

Where U.S. Funds Makes a Difference

The U.S. is helping change that dynamic. Through its backing of platforms like the Inter-Agency Coordination Group Against Trafficking in Persons (ICAT) — a 31-member UN-led coalition — and its consistent support for UNODC operations in over 110 countries, the U.S. is advancing a more coordinated, victim-centered global response.

In Honduras, for example, the U.S.-supported MENTHOR training program helped the government initiate dozens of new investigations and identify at least 150 trafficking victims. “We help draft laws, train prosecutors and build systems that didn’t exist before,” says Chatzis. “The U.S. makes that possible.”

Meanwhile, the U.S. State Department’s annual Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report continues to drive international accountability by ranking countries based on their anti-trafficking performance — and linking those rankings to eligibility for U.S. assistance.

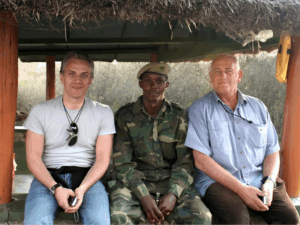

“The U.S. deserves credit for a lot of what’s been accomplished,” says Ilias Chatzis, chief of UNODC’s Human Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling Section. “But we have a lot more to do.”

Ilias Chatzis, UN Office on Drugs and Crime

“No country wants to be seen as weak on trafficking,” Chatzis says. The TIP Report ensures that spotlight stays on.

That spotlight has also helped shift the global conversation toward survivors. “The U.S. worked closely with us to ensure the concept of ‘survivor’ was introduced into international frameworks,” Chatzis says. “That wasn’t the case even five years ago. Now, it’s standard.”

In June, UNODC will convene its first ever Global Survivors Forum in Vienna — bringing together governments, civil society and trafficking survivors to co-create practical, survivor-informed solutions. “It’s about listening — really listening — to the people who’ve lived this,” Chatzis says. “You can’t draft laws or design programs without them. They are the experts.”

Lundstrom agrees. “If all the existing services worked well for everyone,” she says, “trafficking wouldn’t exist. But they don’t.”

She’s now working to close those gaps through both policy and practice. Drawing from personal experience, best practices from UNODC and lessons from U.S. communities, she’s helped shape legislation like the Frederick Douglass Trafficking Victims Prevention and Protection Act — which passed the House in 2024 by a landslide bipartisan vote of 414–11. The bill expands the National Human Trafficking Hotline, supports survivor-led job programs and requires U.S. foreign assistance to integrate anti-trafficking strategies — many of which are reflected in the U.S.-UNODC partnership.

That partnership is especially important in crisis zones, where trafficking risks are magnified. “Whether in Ukraine or Haiti, conflict and natural disasters drive the displacement that increases trafficking risk,” says Chatzis. “And 74% of cases involve organized crime. It’s hard to separate it from drug smuggling or terrorism.”

As traffickers become more sophisticated, the international response must keep pace. UNODC is working with police and prosecutors to identify new patterns of exploitation, advocating for legal reform and urging technology platforms to act faster.

“We can’t arrest our way out of this,” Chatzis says. “We need prevention, education, survivor engagement and technology on our side. It’s an all-hands-on-deck problem.”

“We can’t arrest our way out of this. We need prevention, education, survivor engagement and technology on our side. It’s an all-hands-on-deck problem.”

Ilias Chatzis, UN Office on Drugs and Crime

Making the Invisible, Visible

From its global training programs to coordination of the Palermo Protocol — the landmark anti-trafficking treaty ratified by 185 countries — UNODC’s reach is significant. But its success depends on sustained U.S. leadership.

“This isn’t the trafficking we knew in 2000,” Chatzis says. “It’s more violent. More hidden. More digital. And we need to up the ante — urgently.”

Lundstrom puts it simply: “Trafficking isn’t just about what’s illegal. It’s about what’s invisible. And we have to make the invisible visible.”

Continued U.S. engagement can do just that.

“Trafficking isn’t just about what’s illegal. It’s about what’s invisible. And we have to make the invisible visible.”

Megan Lundstrom, CEO, Polaris Project

Resources

-

Download the UNODC Global Report on Trafficking in Persons

-

Learn more about the U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline at humantraffickinghotline.org. Need help? Call (888) 373-7888