Expert insights from Vincent Valdmanis, Director of Peace and Security Policy for the Better World Campaign

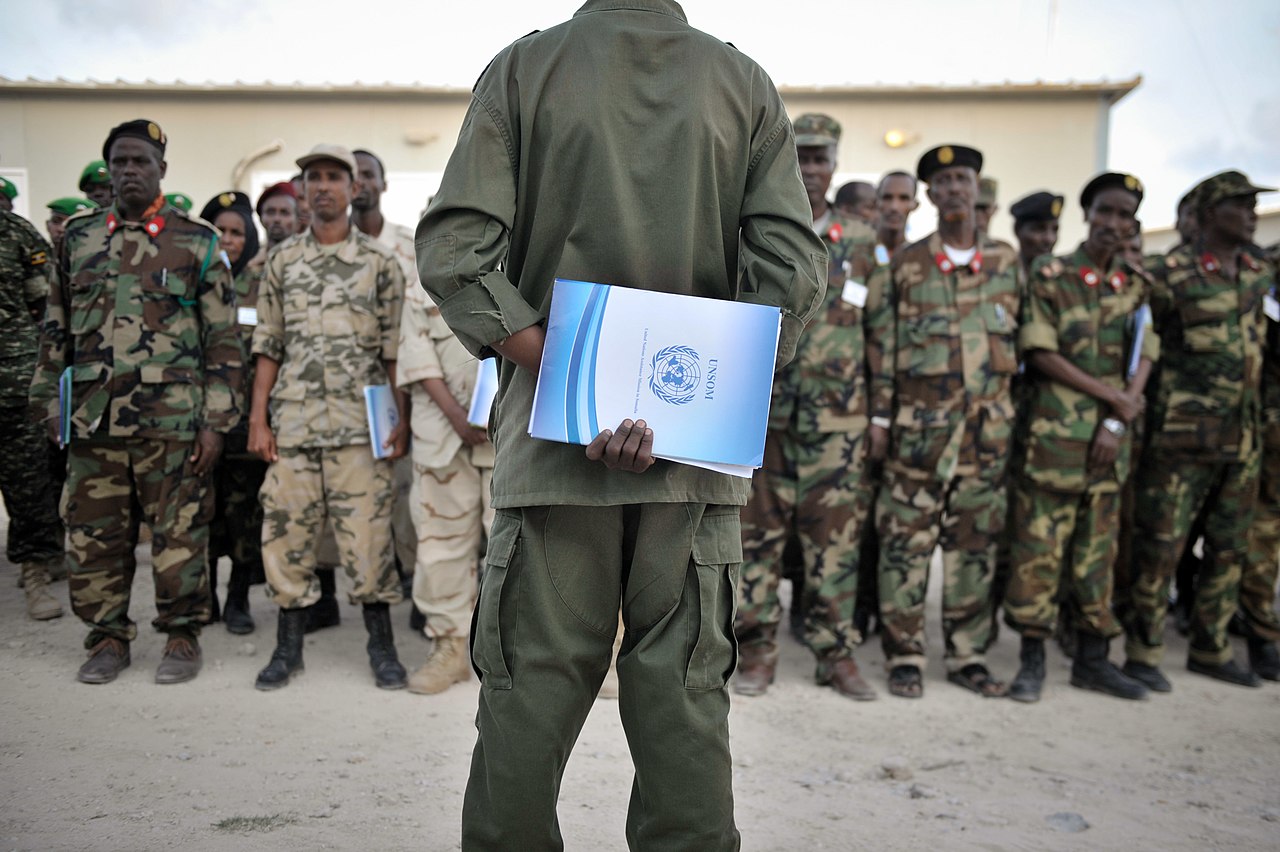

Two UN political missions will soon sunset – the UN Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI), which was established by the Security Council in 2003, and the UN Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM), created in 2013. Not far behind will be MONUSCO in the Democratic Republic of Congo and MINUSMA in Mali which will fully complete its withdrawal in mid-2025.

While the dissolution of these operations may lead some to believe UN peacekeeping is a relic of the past, that would be a mistake. In fact, ending missions is both part of their mandates and part of the principles of sovereignty on which the UN is founded.

The Minutiae of a Mandate

The reality is that dynamics of all missions differ – in type, size, mandate and transition timeline. What’s happening in Iraq, for example, is an orderly and predictable drawdown. In Somalia, regional and domestic political shifts are in play. In DRC and Mali, external actors have stoked disorder and disinformation to actively undermine UN missions on the ground. It’s simply not possible to draw a single conclusion about UN peace operations from disparate cases.

And beyond their widely varying responsibilities, missions also have widely varying capacities and footprints. While MONUSCO and MINUSMA are peacekeeping missions managed by the Department of Peace Operations, which has expertise in protection of civilians and security sector reform, UNAMI and UNSOM are political missions managed by the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs, with expertise in mediation and electoral support. The former have troop contingents; the latter do not. The former had around 15,000 personnel; UNAMI has just over 600. MONUSCO has one of the UN’s largest aviation fleets including military aircraft with offensive capabilities; UNAMI has two civilian aircraft for diplomatic missions to regional capitals.

Comparing missions, then, is never an apples-to-apples analysis. We’re looking at very different populations, challenges, histories and scopes.

“Comparing missions is never an apples-to-apples analysis. We’re looking at very different populations, challenges, histories and scopes.”

What’s more, the Security Council has anticipated – indeed, hoped for – mission closure in Iraq for some time. In May 2023, the UNSC requested the Secretary-General carry out an independent strategic review, resulting in support for a request from the Government of Iraq to pace the closure of UNAMI over a two-year period, ending in May 2026. This transition would be followed by a year-long transfer of residual tasks to UN agencies such as UNDP. The SG’s report also recommended the use of an indicator-based approach for the UNAMI drawdown to reassure Iraqi stakeholders of “the sustainability of the current political system and their continued safe participation in it, with or without the Mission’s presence.” Notably, this concern hints at a less-discussed aspect of UN mission closures – their impact on the influence of external actors and political space for civil society and minority groups within a country.

Taken in aggregate – lest we inaccurately extrapolate beyond the nuance of a single mission – decades of academic research has demonstrated that UN peacekeeping not only works at stopping conflicts, but works better and more cost-effectively than any other option on the table. The GAO has found that deploying UN peacekeeping missions are, at minimum, eight times cheaper than sending in U.S. forces.

“Decades of academic research has demonstrated that UN peacekeeping not only works at stopping conflicts, but works better and more cost-effectively than any other option on the table.”

Rather than dwelling on the closure of UN missions, we are better served by assessing the impact of UN missions. And when assessing impact, we must bear in mind that some of the lower profile missions appear that way precisely because they are successful in keeping conflict from becoming crisis – in short, no news is good news.

As some operations stand down, inevitably a need will emerge for others to be stood up. When they do, the UN will address them following the principle of consent: using tools with well-established records, applying resources contributed by every Member State and in a spirit of solidarity and unique legitimacy to protect civilians and uphold human rights.

And maintaining U.S. leadership through payment of our arrears to the UN will be among our best and most efficient options to maintain international peace and security.