Every three years, the 193 Member States of the UN collectively decide on a formula – known as the Scales of Assessment – to determine how much each country contributes to the UN regular budget and to peacekeeping operations.

Share

The Scales of Assessment: Understanding the UN Budget

FAQs about the UN Budget

Driven by Member States of the UN, the process is a complex and important one. We’re answering ten common questions to help make sense of it all.

-

How is the formula determined?

There are two main budgets of the UN: the regular budget and the peacekeeping budget.

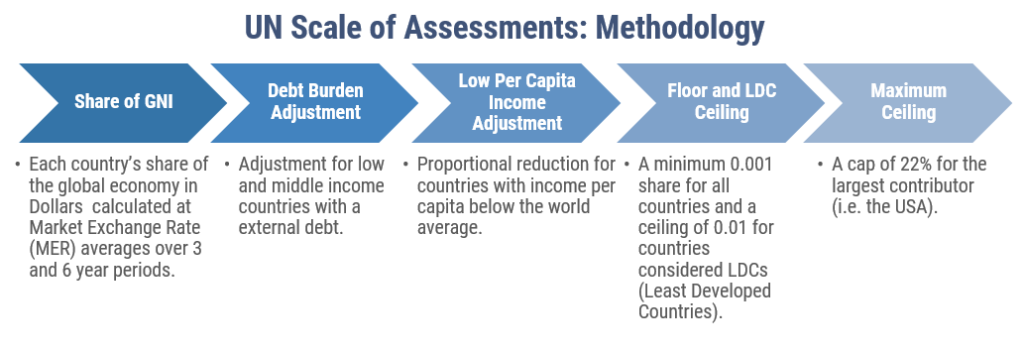

For the regular budget, each country’s contribution is based on a formula intended to represent a country’s “capacity to pay.” The formula starts by using a country’s share of global gross national income. Adjustments are then applied for factors like their debt and population, with a minimum and maximum determined for least developed countries and the largest contributor – the U.S.

The peacekeeping budget is also determined by the formula, but includes additional adjustments, such as whether a state chooses to contribute troops. These discounts are made up for by Permanent Members of the Security Council, who pay a premium that reflects their oversight of peacekeeping operations.

Here’s a closer look at the Scales of Assessment:

-

Shouldn’t countries just pay what they want?

The treaty adopted by the U.S. to become a member of the UN reflects an assessed model for payments – not voluntarily. That’s because voluntary contributions just don’t make sense for an organization like the UN.

Most voluntarily funded organizations have program-oriented missions that are more outcomes-driven in nature and therefore more easily quantified (like delivering food or vaccinating children). Programs funded through assessed budgets, such as those at the UN, tend to be more process-focused and thus harder to quantify.

This is one reason why the U.S. government also has an assessed funding structure for its programs: our taxes. Assessed budgets offer more stability for the payee and the payor, rather than relying on donor funds that often fluctuate.

-

How much does the U.S. currently pay?

As the world’s most prosperous nation, the U.S. is the largest contributor to the UN. The U.S. pays 22% of the regular budget and is assessed at 27% of the peacekeeping budget.

In 1993, however, U.S. Congress placed a 25% cap on American contributions to peacekeeping. That means that although the U.S. is billed at 27%, we pay just 25%. That difference has been building for years, yielding more than $1 billion in total arrears owed to the UN.

-

How much of the U.S. federal budget goes to the UN?

In total, U.S. payments to the UN account for just 0.2% of the overall annual federal budget.

Fun fact: a large latte costs twice as much than the U.S. per capita cost of UN regular budget dues!

-

Is the U.S. typically behind on its dues?

Unfortunately, yes.

Beginning in the 1980’s, the U.S. Congress started withholding part of its contribution to the UN. This reflected U.S. domestic policy debates about the need for UN reform and the fairness of U.S. dues. In 1993, Congress placed a cap of 22% of the regular budget and 25% of peacekeeping.

In 2000, the detrimental impact to the UN caused by the U.S. withholding its full dues, resulted in international criticism and the potential loss of U.S. voting rights in the UN General Assembly. This led to the passage of the Helms-Biden Act that included partial payments of U.S. arrears, along with subsequent payments predicated on lowering the U.S. assessed rate from 25% to 22%, and hitting certain UN reform targets. In the exchange, the U.S. committed to paying $926 million of its $1.3 billion in arrears.

Since the Helms-Biden Act, the U.S. has had a mixed record with regards to fully paying its peacekeeping rate. During the latter half of the George W. Bush Administration, Congress reinstituted a cap, putting the nation back in debt to the UN. Following the election of President Obama, $721 million in peacekeeping back payments were made to the UN, and the U.S. resumed full payments during the first several years of his Administration.

Today, although partial and periodic arears payments are made to the UN, a 25% peacekeeping payment cap remains in place. The U.S. owes more than $1 billion to the UN.

-

What happens when the U.S. doesn’t fully pay its bill to the UN?

The UN cannot simply reduce its spending to offset U.S. nonpayment.

U.S. arrears mean that UN peacekeeping missions are prone to financial strain, which is especially hard on UN troop-contributing countries like Rwanda and Ethiopia, who rely on reimbursements. This also means that essential procurement activities like purchasing life-saving supplies and renting equipment are stalled or cannot be undertaken.

When the U.S. fails to pay its peacekeeping and regular budget dues, it jeopardizes UN programs that are in the U.S. national interest, as well as negatively impacts America’s ability to advance its agenda at the UN.

-

Can the formula be changed?

Yes, but it’s tough.

Although the formula is revisited every three years, countries generally prefer not to open up the negotiations. That’s because it’s a classic zero-sum game; if one country pays less, another country must pay more.

If the UN does opt to adjust the formula, it’s worth keeping in mind that while decisions in the General Assembly usually require a two-thirds majority, decisions on the budget are traditionally made by consensus.

-

Should the formula be changed?

Because the last major change to the formula occurred more than two decades ago, many Member States argue that it’s time to reconsider how dues are determined.

A number of changes have been suggested. One recommendation includes establishing minimum assessments for permanent and non-permanent members of the Security Council, while others have pushed for eliminating discounts for wealthy nations like Kuwait, Qatar, Singapore, and the United Arab Emirates.

To reach any agreement on changes, however, countries must be willing to make concessions. Historically, this has proven exceedingly difficult. Every three years when negotiations occur, the U.S., for example, has called for a reduction in peacekeeping, but then objects when other countries claim that the U.S. shouldn’t receive special treatment on the regular budget. As a result of the U.S. position, little has changed.

-

When was the last round of rate negotiations?

In 2023, the UN assessed the U.S. share of the regular budget at 22% and its share of the peacekeeping budget at 27%. Because of caps to peacekeeping contributions that were set by the U.S. Congress, the U.S. pays 25%. -

Are there really benefits to funding the UN?

YES!

When the U.S. pays its dues on time and in full, other countries are encouraged to do the same – picking up 78% of the tab of the UN regular budget.

And that’s just the economics. The benefits the U.S. receive are incalculable.

Among more than 85,000 peacekeepers, the U.S. provides just several dozen troops and police. These troops are essential to preventing conflicts from starting and spreading.

When emergencies like natural disasters and famine force millions to flee their homes, it’s UN agencies that are on the front lines of the response to shelter, feed, and heal those in need.

Our government can always do better to ensure taxpayer dollars are efficiently used, including at the UN. But this is one place where our small investment pays dividends – just as not paying costs our country in the long run by undermining the UN’s ability to work efficiently.