This weekend kicks off an unusually packed stretch of global sports moments – from Super Bowl LX on February 8 to the Winter Olympics unfolding this month in Milan – at a time when politics feels more heated and civic trust is under strain.

Against that backdrop, Marçal Jané is thinking a lot about what sports can do beyond the scoreboard.

Jané leads sports diplomacy programming at the UN Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR). In a recent conversation, he explained the growing field of sports diplomacy and how we can use these moments for more than a trophy.

Soft Power that Can Change the World

“Sports diplomacy is a tool for the exercise of diplomacy,” Jané said. “It’s a potent form of soft power.”

He points to a definition from scholar Stuart Murray that he finds especially practical: the strategic use of sport to bring people, nations and institutions closer together through a shared love of physical pursuits.

“Sports diplomacy is a tool for the exercise of diplomacy… It’s a potent form of soft power.”

Marçal Jané, Sports Diplomacy Programming Lead, UNITAR

It’s a framing that most spectators intuitively understand. After all, many of us are familiar with the “ping pong diplomacy” of the 1970’s – a chance encounter between President Nixon and China’s Mao Zedong credited with kicking off formal diplomatic relations between the two countries (famously memorialized in Forrest Gump).

In divided times, Jané says, sporting events remain one of the few public spaces where people still gather despite differences to experience something shared – and this shouldn’t be taken for granted.

Jané often returns to the words of Nelson Mandela, who said that “sport has the power to change the world.” The phrase has been quoted into cliché, but Jané insists it still holds.

And Mandela would know just how much sports could make a difference. In 1995, South Africa hosted the Rugby World Cup, the country’s first major post-apartheid sporting event. When his country won, he presented the trophy wearing the jersey of the once all-white national rugby team. Even today, it’s regarded as one of the most iconic moments in sports history.

“Fact is, sports are a powerful convener – a non-politicized, neutral entry point for dialogue,” Jané contends. “That matters when many of our institutions are ignored.”

“Sports are a non-politicized, neutral entry point for dialogue.”

A Decade of Sport

All of this is especially important as the U.S. enters what’s being called the “Decade of Sport.” Between the 2026 FIFA World Cup, the 2028 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games, the 2031 and 2033 Men’s and Women’s Rugby World Cups, and the 2034 Winter Olympics and Paralympics, the calendar is crowded with moments that will place American cities – and American values – under a global microscope.

“This is a rare opportunity to shape how the U.S. presents itself to the world,” Jané notes.

“America’s Decade of Sport is a rare opportunity to shape how the U.S. presents itself to the world.”

Mega-events, he argues, aren’t just broadcasts. “They have incredible convening power, and the essence of multilateral diplomacy is convening.”

They also create space for parallel diplomacy – informal exchanges that unfold on the margins. One recent example came in November 2025, when friendly matches between teams from Catalonia and the Basque Country against Palestine doubled as quiet diplomatic encounters, with ticket proceeds directed to humanitarian initiatives supporting victims of the war in Gaza.

Ambassadors Take to the Field

If arenas are the diplomatic terrain, Jané says, athletes are their ambassadors.

“Athletes can’t be treated as an afterthought,” he stresses. “Their visibility is a core source of sport’s power.”

Jané adds, “Fans take cues from players about values, whether institutions intend it or not. They need to understand the image they’re projecting.”

Jané says he watches athletes’ symbolism closely: gestures, apparel, moments of silence – all of which can carry political meaning. From NFL players taking a knee to diaspora athletes navigating unresolved historical grievances, sports routinely become a proxy battleground for identity politics.

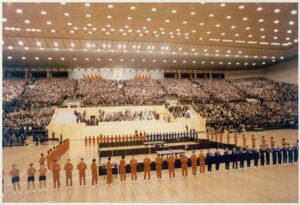

He recalls the famous image of South Korean bobsledder Won Yun-jong and North Korean women’s ice hockey player Hwang Chung-gum marching together under a single flag at the Olympic Games – an extraordinary moment of unity set against a conflict that has persisted since 1950.

“They delivered a simple yet powerful message to the world: we want peace. In that quiet, symbolic act, sport cut through decades of division.”

“In that quiet, symbolic act, sport cut through decades of division.”

Their actions were a reminder, however fleeting, that even when conflicts remain unresolved on paper, people can still choose to signal hope, dignity and the possibility of another future.

“These stories don’t stay on the field,” Jané said.

The Role of the UN

Ask which UN body works on sports and many people will name UNESCO. Jané credits that history, but says the footprint is much bigger.

“People would be surprised by just how many parts of the UN system are involved in sports,” he said. They show up in public health through the World Health Organization, in social integration and trauma recovery through the UN Refugee Agency and in crime prevention through the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. UNICEF, too, uses sports to support children’s physical and emotional recovery in conflict and displacement, while UN Tourism helps governments foster economic growth through sports.

“The bigger point,” Jané said, “is that sports touch health, education, inclusion, youth development and social cohesion in a way that doesn’t require major government support.” He also references civic groups that intersect with the UN like parkrun – the world’s most successful, free community sport organization. The network of organizations is vast.

“People would be surprised by just how many parts of the UN system are involved in sports… health, education, inclusion, youth development and social cohesion.”

Where UNITAR Fits

Like the necessity of having a good coach, UNITAR serves as the UN body that exists to train.

“At its core, UNITAR’s sports diplomacy programs helps people looking to use sports for good understand what works, what doesn’t and how to design programs that are truly impactful,” Jané said.

The institute’s courses intentionally mix players, diplomats, civil society leaders and private sector voices. That diversity, he argues, helps people see sports not as a standalone activity, but as a bridge capable of breaking down silos and building more unified approaches.

And it’s no mistake that work sits within UNITAR’s Division of Multilateral Diplomacy, as sport is inherently a multilateral, multistakeholder endeavor. Rabih El-Haddad, the division’s director, put it plainly, “Sports is a natural connector where traditional spaces may feel too stifling,” he said. “I’ve seen plenty of tense negotiations loosen up over lively debates about the previous night’s soccer match. It’s just so human.”

“I’ve seen plenty of tense negotiations loosen up over lively debates about the previous night’s soccer match. It’s just so human.”

Rabih El-Haddad, Director of the Division of Multilateral Diplomacy, UNITAR

More Than a Game

Asked how sports could better serve the public good, Jané pointed to the need for institutional seriousness. One proposal he supports is the creation of sports diplomacy strategies by all countries worldwide, led by country and even state-level “Sports Ambassadors” to legitimize and professionalize work that already happens informally – an idea many lawmakers have embraced. He cites U.S. Congresswoman Rep Kamlager-Dove’s efforts to shepherd sports diplomacy, which have gained traction through the 2025 American Decade of Sports Act, passed in December 2025.

“These moments are already diplomatic,” Jané said. “What we need to think about now is how will we use them in the service of diplomacy and development.”

Because when final whistle blows on competitions in the weeks and months ahead, he reminds me, the question won’t be who takes home the trophy, but whether we seized the chance to harness the power of sports to achieve something much larger than a game.